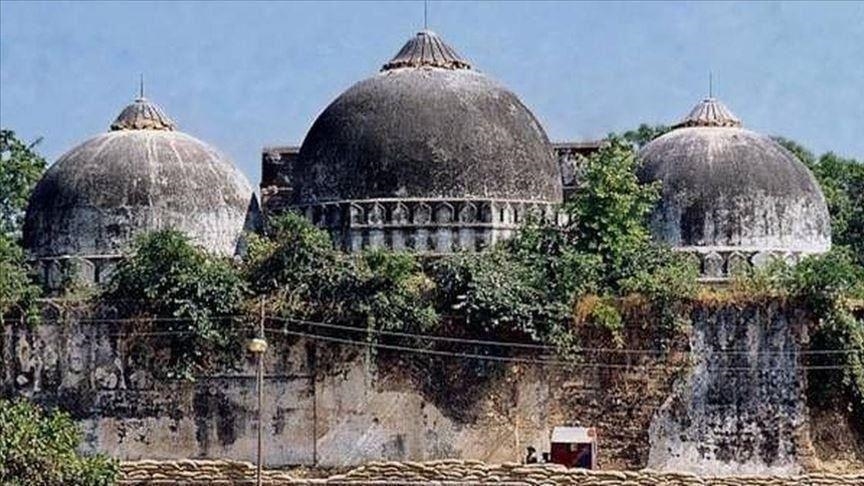

New Delhi: In a statement that contradicts the 2019 Supreme Court judgment on the Ayodhya land dispute, former Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud has stirred a fresh controversy by asserting that “the very erection of the Babri Masjid (in the 16th century) was a fundamental act of desecration.”

Chandrachud was one of the five judges on the bench headed by then‑CJI Ranjan Gogoi that, in November 2019, cleared the way for the construction of a Ram temple at the disputed site in Ayodhya. At the time, the Supreme Court had allowed temple construction but explicitly stated that the archaeological evidence could not definitively prove that the mosque was built by demolishing an earlier structure.

During an interview with journalist Sreenivasan Jain for Newslaundry, Chandrachud referenced the findings of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and maintained that while the legal weight of archaeological excavations is limited, the evidence still exists and should not be ignored. “There was adequate evidence from the archaeological excavation,” he said. “Now, (what’s) the evidentiary value of an archaeological excavation is a separate issue altogether … all that I want to say really is this — there is evidence in the form of an archaeological report.”

When asked about the issue of inner courtyard trespasses, Chandrachud pushed back on critics who emphasized Hindu “desecration and disturbance” in parts of the disputed land, asking instead why attention was not equally paid to what he described as the original act of desecration — the building of the mosque itself. He also accused commentators of adopting a selective narrative of history, ignoring inconvenient findings that predated the mosque.

However, Chandrachud was emphatic that historical evidence does not justify the 1992 demolition of the mosque. He defended the Supreme Court’s 2019 decision, saying it adhered to legal principles such as adverse possession and conventional evidentiary standards, rather than relying on faith or religious arguments. He challenged critics who accused the judgment of being faith-based, saying they had not actually read the full decision.

The 2019 verdict had explicitly noted a centuries-long gap between the 12th‑century structure uncovered in excavations and the 16th‑century mosque, and observed that there was no solid record of demolition or construction of the mosque during the intervening centuries. Hence the ASI report alone could not establish title.

Chandrachud also addressed the Gyanvapi Mosque case, explaining that the Supreme Court allowed a site survey despite legal protections because the religious identity of the property was not yet settled. He claimed Hindus had “undoubtedly” worshipped in the mosque’s cellar over time — a claim Muslims contest.

On Jammu & Kashmir, the former CJI defended the reorganisation of Indian‑administered Kashmir, citing national security as a legitimate ground for sweeping policy decisions. He also rejected rigid constraints on post‑retirement roles for judges, implying that each must make their own choices unconstrained by doctrinaire rules.

Chandrachud’s remarks have rekindled debate over India’s legal, historical, and religious discourse around the Ayodhya dispute and beyond, highlighting the ongoing tension between historical interpretation and legal jurisprudence.

Leave a comment